Part of the life of the society in which it develops and on which it has an impact perhaps not always fully assumed and respected, the school benefits both from the scientific structure and from the tendency – natural and necessary – to investigate the new. So how do we deal with the digital reality that students live in and that even the most conservative of teachers can’t dissociate themselves from? Here is the plot of this work!

In this context, the purpose of this work is to investigate and assess the impact of online schooling on Romanian grounds, following the opinions of the three active educational performers immerged in it the most: teachers, pupils, parents. The inquiry has followed the primary education learning path, as part of a deeper concern for this field, with an open eye towards both achievements and challenges. The questionnaires have given the possibility to all three categories to express personal perspectives and conclusions.

The reasonable deduction of the present educational approach is that online courses represent a milestone in the functioning of Romanian schools, providing us with the ability to acknowledge the importance of both direct interaction and need to develop acquires in terms of technology.

____________________

Journal of Digital Pedagogy – ISSN 3008 – 2021

2024, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 29-39

https://doi.org/10.61071/JDP.2462

HTML | PDF

____________________

Introduction

The school has been at the heart of many debates in recent years, but even more so during the Covid-19 pandemic. Medical considerations, concerned with the health of the population at the global and local level, the need to adopt restrictive measures to limit the spread of the virus, the gradually acquired knowledge about the susceptibility of children and young people to the virus and its transmission capacity have intertwined – and sometimes they faced – the needs of the educational environment.

School, neuropsychiatrists specialized in pediatrics emphasize, represents a fundamental dimension of children’s lives, not only as a matter of learning, but also important in socialization, peer comparison, as a reference of significant adults outside the family’s comfort zone.

Viewed from a generic perspective, the educational institution is intended to cover and naturally satisfy the requirements of all those it addresses, regardless of origin. Therefore, the educational policies that increase the value that the school has in society are fundamental. Access to education is a tool that must serve us to fight ignorance, discrimination and ensure a better future for children, because “if you have only one block of marble and you use it for a caricature, where else can you carve a Minerva?” (Steinhardt, 1991).

Unlike the previous stages, the current education has come to positively influence various categories of disciples, addressing the disadvantaged as well. In fact, the very operation of educational institutions and those who facilitate this process is statutorily conditioned by the principle of non-discrimination and equal opportunities. This reality represents a huge step in the diversification of the educational field, compared to the situations previously encountered.

We note that the present is characterized by an accelerated expansion of the educational field, in which the central actor – the student – has at his disposal a complex of opportunities: nurseries, kindergartens, schools, institutes, universities, etc. A determining factor of the multitude of educational offers is represented by the increasingly strong rise of the virtual learning environment, which can be included in the online school. The options presented in a widened educational field support individual development, but the cumulative effort is greater, due to the volume of activities chosen: the calendar of a current learner may include compulsory lessons imposed by the educational institution in which he works, optional courses, extracurricular sessions, hobbies, etc.

In this context, a agreement decree is fundamental, so that there is an interconnection, assumed by all actors, between the educational and social fields. The communication bridge between the two entities will have to cross the virtual realm so feared in the school. The only way is to look at the new technologies of information and transmission of information (ICT) as adjuncts in the educational process – flexible, adaptable, free of conventionalisms, offering openness and freedom to learning options, both for teachers and students. The active involvement of students is essential to their educational process and beneficial to the education system, which pursues the ultimate educational goal: the integration of young people into society. This goal can only be achieved when we abandon the idea that the objects of study are fixed and detached from the children’s experience, and that they only have to respond to requests, without participating with their own voice/action. By activating digital practice in the learning process, the development of personalities capable of solving life’s problems through association and cooperation, in real contexts, can be supported.

The alarm signals currently appearing regarding online activity demonstrate the need to urgently improve the situation, in the direction of achieving an epistemic and functional reconciliation between school and ICT: “Pandemic pedagogy has placed a great emphasis on the principle of continuity of learning. Let’s continue to keep the relationship and the educational community, that’s very important”. In this sense, it insists on “individual and collective responsibility” alike, to nurture the reality of a transformed classical educational field – the teacher gained pedagogical autonomy, but “lost the school community between the walls”. Conjunctural and mandatory alike, it becomes essential for the actors of the educational relationship – teachers, students, parents – to coexist, at a distance, supporting each other with more determination, so that the act of learning can be maintained and continued.

Located in an extremely sensitive generalized context, marked by the persistent problematization of health and personal and community safety, the online school phenomenon requires teachers not only to teach, but especially to support the young students emotionally. At an overall assessment and consideration of the increasingly significant technological progress, of the changes in the aspirations of the new generations, it is natural to see the need to develop new ideas, based on the alternation of pedagogical methods. The changes in the living mechanism represented by society outline the new paradigm to be taken into account: the school must recover from this “lack of confidence towards non-formal and informal education, towards its educational-axiological consistency”. In conclusion, “it is necessary to achieve a “constructive partnership” between all these new components of the social field of education, under the auspices of the school, which should assume the leadership of this partnership” (Păun, 2017). This is, moreover, the direction to which international bodies such as UNESCO are currently urging, showing the “undeniable need for collaboration, solidarity and collective action for the common good”, at the centre of which must be “the interests and capacities of the learners” (UNESCO, 2020).

The research, the results of which are presented below, was carried out in early 2023, with specific samples of:

- 50 teaching staff: 74% urban, 26% rural; 50% first professional degree, 32% second degree, 10% final, 6% debutant, 2% substitute; 92% female, 8% male

- 60 students from the primary cycle: during the online school period, students in the 2nd (16.7%), 3rd (41.6%) and 4th (41.7%) grades

- 50 parents: 70% female, 30% male; 12% from rural areas, 88% from urban areas.

Teachers’ Opinion about Online School

Specific to human beings especially in terms of “conscious and intentional relationship with otherness”, communication represents “the essential process by which (man) becomes what he is and enters into relationship with others” (Sălăvăstru, 2005). In a didactic context, communication situations vary depending on the context created for teaching-learning activities. Perceived and assumed as “a complex set of specific didactic actions and behaviours, intended to produce learning”, teaching requires a certain technical skill on the part of the teacher/ student, as well as the mastery of appropriate work tools.

In all its meanings, this essential process in the formative process of students in educational institutions requires, first, the “identification of the role of the teacher” as a determining factor both in the initiation of the cognitive process, and especially regarding the involvement of students in the pedagogical act (Marzano, 2015). By means of high-level cognitive organizers (expository, narrative, illustrative, scriptural) and the “anchors” offered to the class, the teaching staff must ensure students’ familiarity with the new information presented (Marzano, 2015). Using the “principle of small steps” (Rosenshine, 2002; apud Marzano, 2015), which allows the division of the subject into easier to assimilate content units, as well as specific macro-strategies, the teacher has the chance to achieve satisfactory results.

On the other hand, however, what may seem natural and constructive – the congruence of the elements that create the educational contexts necessary for the harmonious development of the disciples – can turn into real blockages when intrusions appear that limit the students’ freedom of expression. According to the opinion of the majority of 42% of the teaching staff participating in the research, technology perceived as an educational resource represented an impediment rather than an adjunct during the pandemic, the causes being multiple:

- Lack of organization at system level

- Insufficient training of teaching staff for the online scenario

- Insufficient equipment

- Poor internet connection

- Problems with the operation of the national platform

- Problems connecting students to classes

- Background noise from students’ homes

At the level of the current development of society, the presence of technology in educational institutions has become a habit, and its integration in the instructive-educational process depends, to the greatest extent, on the desire to use it, on the experience and skills of the teaching staff (Farjon, Smits , & Voogt, 2019). According to the information received from teachers in rural schools, in this environment there is a strong need to have a technical and methodological base adapted to new trends. Only with the right tools and benefiting from the appropriate training, the people from the department believe that the modern technique could be used properly: “If we still have to work with the technology, we should have everything necessary”, concludes one respondent.

The open-ended responses reveal another interesting aspect to mention: many of the teachers’ impressions refer rather to a moderate positioning in the retrospective analysis conducted in the present study. Some of the indications, surprisingly, reflect a common perspective: online school as a breakdown solution or compromise solution. The case deserves to be followed more closely, given the nuances that this subject presents. In this case, we are talking about a 38% share of respondents, who approach the matter from various points of view:

- It is a variant of carrying out the activity.

- It is inappropriate for the primary age segment.

- The online school is a temporary solution – an emergency solution – for emergency situations in case of illness or other issues, school under renovation etc.

The questionnaire dedicated to teaching staff also brings to light a completely antagonistic perspective to the investigative approach, because the respondent we are referring to believes, firmly convinced, that: “We cannot speak of such a concept” – in other words, the online school does not exist! We mention that it is the only voice drastically positioned against the idea of schooling through activities with digital support, but without providing us with details for explanation.

In the context of obvious dissatisfaction with the analysed experience, it is understandable the imperative demand of the teachers to benefit from optimal working conditions. The request becomes imperative in the perspective of a digitized future, according to the trends of society and the improvement directions that teachers are taking. In the words of one survey participant, “We, the more experienced staff in the department, suffered because we didn’t get enough digital training.” Regarding the distribution by age categories, the questionnaire indicates different weights, with major values in the range of 45-54 years (30%), 55-68 years (28%), 35-44 years (26%), respectively minor in the age categories at the extreme poles: 19-34 years (14%) and over 68 years (2%).

According to the psychology of ages, what we generically call the third age begins after the interval of 64-65 years, approximately, being correlated, most of the time, with the moment of retirement (Thalhammer et al., 2014). This existential point represents, including for teachers, a significant event, on a personal, professional and social level. In terms of enabling a “sense of self-control” (Windsor & Anstey, 2008), some teachers tend to stay in the classroom to maintain a lively connection with the school environment that they say is their source of inspiration. The metaphor is interesting, all the more useful in the context of this research, being used by a lady with significant experience in the field, who agreed to answer the questions on one condition – that her opinion be mentioned by another, younger person: You write, my dear, I can’t handle digital intelligence, I prefer the living one!

In the light of these words that start from the contradiction person vs. technology, the conclusion of a study that highlights a reality with sociological implications is significant: people who choose to show a positive attitude in relation to technology will resort to it more often, compared to occasional users or those who reject it (Al-Gahtani & King, 1999). The reasons for the reluctance can be found in the answers of the teachers who indicated the connection problems, the minimal or non-existent facilities to be able to connect with the students at home, the absence of specialized training that would allow them to use the technology without problems.

We found that the objective obstacles during the online school period were also mentioned by teachers from younger age groups than the seniors who found the interaction with the virtual environment to be rather difficult. Thus, the results related to the perception of specific aspects denote the degree of personal preparation that each of the respondents considers having achieved:

Table 1

Aspects of the online school, as perceived by primary school teachers

| To a very large extent | To a great extent | To some extent | To a small extent | To a very small extent | |

| This period gave us the possibility of flexible activities – students could learn when and how they wanted | 12% | 28% | 38% | 18% | 4% |

| It was more convenient, because I no longer travelled to school | 30% | 32% | 22% | 6% | 10% |

| It was easy for me to work exclusively with digital technologies | 14% | 30% | 14% | 15% | 27% |

| I think online school is a temporary solution | 72% | 24% | 2% | 2% | – |

Quite unexpectedly, we find that the share of positive perception on the ease of working with digital technologies is, in fact, at a distance of a few percentages in relation to the negative perception, but unanimity is evident on the temporary nature of schooling in the virtual environment. We also note the high percentage of understanding the situation as an opportunity to stay in the comfort of your own home.

The organization of learning in the exclusively online environment has elicited interesting reactions, especially if we notice the arrangement of the graph in certain points that some of the respondents considered important enough to mention in the detailed answers: the opportunity for professional development, the learning pace of students, technical resources in the pandemic. The teachers’ assessments regarding these aspects were as follows:

Table 2

Primary school teachers’ opinions regarding the organisation of learning in the online school period

| To a very large extent | To a great extent | To some extent | To a small extent | To a very small extent | |

| It supports students in maintaining the pace of learning. | 14% | 30% | 28% | 21% | 7% |

| Provides the opportunity for professional development through the use of digital technologies. | 48% | 32% | 20% | – | – |

| Online activities create an impersonal learning environment compared to the classroom. | 17% | 26% | 32% | 17% | 8% |

| I have benefited from sufficient resources to be able to support the courses in digital format. | 26% | 26% | 5% | 17% | 26% |

In other words, the teachers’ opinion about the exclusively-online school is that it can support the pace of student learning, provide professional opportunities for practitioners, but can create an impersonal study climate compared to the classroom. This is also the reason why, in the free-response section, some have insisted that this type of learning is not suitable for the long-term primary cycle, but rather for certain activities integrated into the lessons. As for the provision of the necessary resources to support online courses, the majority of teachers declared themselves satisfied, which makes us believe that, based on their origin, predominantly from the urban environment, they benefited from the support that their colleagues from the rural area complained about insufficient or even non-existent.

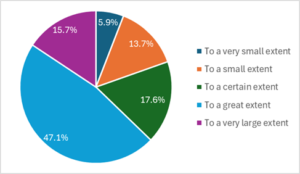

Regarding the general impression on the personal adaptation of the teachers to the conditions characteristic of the period of online studies, the collected information shows us unexpected results, perhaps, if we consider the imputations brought to the system and the organization of the whole context. Thus, out of a total of 51 people, the majority returned to a positive perception of the situation: 47.1% believe that it succeeded, to a large extent, while 17.6% of the teachers declare to some extent satisfaction at the adaptation level; 15.7% announce their adaptation to a very large extent, 13.7% state this to a small extent, and 5.9% indicate to a very small extent self-satisfaction in the new school context.

The teaching staff stated that they suffered quite a lot as a result of technical and organizational inadvertences, they consider the online school a temporary solution, rather a complementary element in the structure of learning in physical format. However, teachers assume the need to adapt to the new, remain consistent with the good of children dependent on the socialization that allows them to develop harmoniously, and consider online schooling at young ages suitable for a well-determined period.

Students in the Virtual Environment

According to specialists, interaction with the class “presupposes a complex set of skills”, the most important of which is the teacher’s ability to create personal connections with each of his students (Cozolino, 2017). By facilitating a safe attachment, within working circles strengthened on mutual respect, cooperation and empathy, the teacher will gain an important place not only in the educational process, but also outside the physical perimeter of the school, because “emotion determines the quality of the recording” information (Cury, 2018). It is essential, therefore, that every active teacher – or willing to become an involved part of this profession – understands the importance of personal connections in a student’s life.

In proportion to 66.7% of the total of 60 respondents in the questionnaire for students, primary school students indicated that they attended all the lessons they were informed about, while 25% encountered technical problems and did not they were able to connect every time. Those who did not show up for any virtual meeting with the class means a percentage of 8.3% in this case.

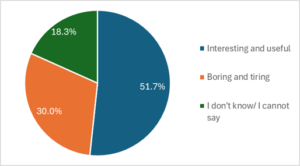

Online learning activities were considered interesting and useful by 51.7% of respondents, uninteresting and even tiring by 30%, while 18.3% answered Don’t Know/ Not Applicable. It is worth remembering, at this point, the fact that the teachers affirmed their satisfaction in relation to the activities they were able to develop in the online school, an aspect confirmed by the surveyed students.

Regarding the preferences related to the learning carried out in the virtual environment, the convenience of working from home meant an impressive majority weight (75%), and the flexibility of activities registered a percentage of 40%. The accessibility of classes and aspects considered to be interesting bring together 38.3% of all respondents, while 5% of them state that involvement in the virtual school was not possible.

The emotions felt by the students, whose memory made the following graph possible, clearly cluster around the idea of relaxation during online classes. 80% of the students declared themselves relaxed in the online school, compared to the remaining 20% who responded negatively. Conversely, a percentage of 43.3% specified that they felt frustration, but also confidence that things will turn out well, but the majority of 56.7% said that they did not go through these states. 70% declared themselves bored with online courses, compared to those interested – 30%; 55% were dissatisfied, 45% – satisfied, but hope was felt by 43.3% of students, compared to 56.7% who declare the absence of this state. However, it seems that staying at home and free activities were more to the liking of the little ones, given that 56.7% felt satisfied with the situation, compared to the difference of 43.3% who denied satisfaction in the analysed period.

Contrary to the opinion of teachers, who considered online school only temporarily useful and unlikely to be effective in the long term in grades I-IV, students seem to prefer (53.3%) rather to stay at home, without classes or homework, in the idea that he recovers later, if he were immobilized or had a contagious disease. In contrast, the difference of 46.7% preferred the proposal to connect online with video in class and attend classes with colleagues.

In the open-answer section, we discovered – similar to the situation in the questionnaire addressed to teachers – varied opinions: 18.3% stated that it was difficult for them, due to connection problems, which indicates a significant difference of 81, 7% who managed to connect to the courses in virtual format. Students also identified the fact that they no longer had to travel to school, 2% emphasizing the convenience of working from home, while the group at the opposite pole (98%) would have preferred to continue attending classes in physical format. It is very interesting to check the correspondence between the teachers’ statements – online school is not suitable for young school ages in the long term – and the opinion of the students, who complained about the need to socialize with the class. There were, however, voices (5%) who probably took advantage of the anonymity ensured by the present study (respecting the GDPR rules in force, it did not retain personal data from the respondents), to express their delight in playing on computer during online classes. However, 40% of children declared themselves satisfied with online learning, which they consider interesting, even useful “under certain conditions”. Similar to the case of the teachers, one of the respondents wanted to express his opinion by offering an overall perspective: “It was a challenge, sometimes difficult, because it took me a while to understand how to proceed with some topics, then it became very interesting, because the lady gave us all kinds of interesting games and we were able to learn differently than in school”. As a continuation of this idea, another student concentrated in a suite of concepts the belonging to Generation Z and the direction towards which society is heading: “Normality – Evolution – New Generation”.

Parents during the Pandemic

The presence of the students in the online school was also confirmed by the adults in the family. Out of a total of 50 people, 58% answered yes to the question During online courses, did your child participate in learning activities?, compared to 36% of parents who indicated technical problems and partial connection. In fact, this fact was previously discovered in the statements of the teachers and students questioned. In proportion to 4% the children did not participate for other reasons, and for 2% the reason was personal and strong enough to avoid connecting: the activities did not seem interesting to one of the students.

The perspective of adults on the new study situation of their own children specifies, in an impressive majority of 80%, the fact that online school is a temporary solution, that the comfortable environment at home has taken them long enough (52%) to reach to appreciate the flexibility of the work schedule (38%). As a result of the lessons being held in a digital format, the family was able to have direct access to the activities by attending the classes, which led some parents to find the lessons accessible and interesting (28%). Some parents, however, said their son/daughter did not participate in online school (4%).

Regarding particular situations, such as: in case of illness, to protect the rest of the class, in case of immobilization in bed after an injury, etc., parents declared in unison – 86% of respondents – that online learning would be useful, compared with 14% negative responses to this question.

The emotions experienced by parents during their children’s digital schooling were variously distributed regarding the statistical data. Relaxation was felt as follows: 38% to some extent, 24% to a very small extent, 22% to a small extent, 8% to a large extent, 8% to a very large extent. According to these figures, we can consider that the families did not feel the relaxation to the same extent as their own children, even if they previously stated that they found it convenient for the students to stop going to school.

Frustration affected 28% to some extent, 26% to a very large extent, 20% to a small extent, 16% to a large extent, 10% to a very small extent. It seems that this emotion was also a sensitive point, to which dissatisfaction was added, to a very large extent (38%), with a percentage of 28% to some extent, 14% to a great extent, 12% to a very small extent measure, 8% to a small extent.

In this context, boredom appeared to a very small extent (30%), but 28% declared that they felt it to some extent, 22% to a small extent, 12% to a large extent, 8% to a very large extent. We can therefore deduce that the families did not consider this emotion to be meaningful in the courses in the virtual environment, and perhaps it would be interesting to investigate, precisely, what were the causes for which the present analysis recorded such statistics.

The positive emotions experienced by parents indicate a significantly moderate weight (to some extent) of the level of: trust (50%), hope (34%), satisfaction (34%). Similar values of 20% were recorded in relation to the minimum levels of trust (to a small extent, to a very small extent), instead, differentiation was evident in how people felt the absence of hope (22% to a very small extent; 20% to a small extent). With such benchmarks, we would discover a rather low level of satisfaction during the period under investigation (34% to some extent, 30% to a very small extent, 22% to a small extent).

According to the graphs resulting from the parents’ survey, the three emotional benchmarks that support the positive projection of reality show reduced values at maximum levels of perception: 6% answered that they felt trust to a great extent, alongside 4% who declared it very great measure; hope: 14% to a great extent, 10% to a very great extent; satisfaction: 12% to a great extent, 2% to a very great extent.

The opinions identified above culminate in the overall impression of the online school expressed in the free-response section. Thus, in a majority of 44%, parents wanted to sound the alarm about a series of negative aspects such as:

- technical malfunctions;

- the absence of the necessary equipment for each student;

- the state of tiredness/illness that the child accused after being involved in the virtual classes;

- the lack of sufficient training of teaching staff in the online field, which significantly hampered the quality and results of the respective activities.

The moderate impressions referred to the compromise aspect in which the majority of the population was at global level, and the arguments were, on the one hand, the importance of continuing the courses in a suitable form, on the other hand, the need to respect the regulations of the moment. Those who fell into this trend represent 40% of parents, who claim that we are discussing a “viable option only in exceptional situations”. For 24%, physical school is oppressive, while 16% believe that online school is “not a beneficial solution” for primary school students.

Conclusion

It is true that interaction in the classroom differs from that conducted digitally, but both environments involve a three-dimensional interaction of students: with the object of study, with the teacher, with the group of peers. According to the verifications carried out through the present research, the difficulty online consisted, as in other corners of the world (Gunawan, Suranti, & Fathoroni, 2020), in: problems of a technical nature, faulty organization of the initial period, as well as in the absence of some previous exercises from the teaching staff. These are, moreover, the first areas of criticism that all three categories of respondents – teachers, students, parents – indicate as urgent for remediation. Practically, “the transfer of the traditional face-to-face learning system to the online environment without proper training was one of the problems of education in this pandemic period” (Ceobanu at al., 2022).

Regarding participation, the availability of students was higher than that of adults, which led to the analysis of a sample of 60 responses compared to 50 for each of the other two target groups. We saw it as a real opportunity to be able to record the views of the children, who thus had the opportunity to express their ideas in complete freedom – perhaps this is why they explained in less elegant terms their rejection of the online learning context. Further investigations, complementary to the written questionnaire, revealed a reality about which complex strategies of action could be developed: the educational crisis in which students find themselves who prefer to consume their time with anything else besides the educational process. In other words, those who did not want to study in the classroom, much less will look to connect online, in a window on the teacher’s monitor who must simultaneously manage an entire work group and possible technical syncopes.

On the other hand, however, the voice of those who want to study and openly confess this, suffering from the impossibility of socializing within the student body, is just as real. The open attitude to learning is also openly supported by parents who clearly show their preference for physical school and to avoid the online environment in the long term.

The context opens the way to an approach that some of the teachers interviewed after completing the questionnaire adopted: the caution of using the digital domain in the instructional-educational process. The reasons are related to personal observations and the information that circulates online about the involvement of students in the virtual: “the presence on social networks is one of the factors that can positively or negatively influence the educational performance of students” (Ceobanu et al., 2022). At the level of the three classes discussed in the present research – 2nd, 3rd, 4th – this might be unlikely to happen frequently. But we don’t know how valid the assumption remains in the older classes, because middle school students have permanent access to smartphone devices from which they completed the questionnaires analysed here…

We mentioned the care for the children’s well-being previously and we consider it opportune as a common point of discussion between the two camps: teachers – parents. Obviously, both groups found the difficulty of the students to endure for a long time in the solitude of their own home, without the possibility to socialize with the group and with the others in the educational institution. The desire to physically return to classes was also highlighted by students who declared themselves satisfied with the way the classes were conducted in a virtual format, which confirms the reconciliation discourse that the specialists approach: teachers “understand the fact that the generations present shows more and more resistance to the routine promoted by the school, which leads them to reconsider their pragmatic value” (Ceobanu et al., 2022). So, the proposed solution for the good of all is for digital elements to be part of the structure of classroom lessons.

Another common direction of statistics considers the need for online learning to remain possible in exceptional contexts, such as medical problems or any other situation that does not allow a student to travel to school. All three categories showed that there are situations that require material recovery, parents insisting that it would be useful to connect immobilized/ sick children from home to online courses. Here, however, it is interesting to individualize the distinct opinion of the students, who prefer to recover later if they stay away from school. The contradiction gives rise to new concerns and the attitude I mentioned above seems to become recurrent, so we can launch a question with potential for new research: Why do today’s students prefer to avoid school? And, perhaps along with the answer to this, at some point we will also be able to understand how to support their curiosity and motivation to continue learning.

Regarding continuity, it is important to mention that the majority of respondents indicated that there was information from the institution, through the teacher, to the beneficiaries – the students, and the latter were able to get in touch with the class online. The fracturing of this connection is, as we have noted, an Achilles’ heel in virtual schooling, as “there can be no expectation of learning gains simply by introducing ICT into schools” (Kozma, 2005). This is, moreover, the opinion of the teaching staff, who continue to use technology according to their own level of acceptance and openness to the new, not necessarily due to an expertise based on a suite of specific training activities in the online field.

Technology is a real educational resource, but the direction and extent of openness to integrating it into current learning activities is fundamental – recent research has shown that the success of an integrated approach directly depends on teachers’ “willingness to use technology, experience and skills” (Farjon, Smits, & Voogt, 2019).

Resistance to change cannot be considered an impediment to Gen Z disciples, who end up assisting their masters in situations that require digital knowledge – they are teachers who declare themselves equally amazed, pleased and, to some extent, intimidated by the prowess of their students who know how to solve everything from or with the buttons. Regarding the teaching staff, however, things are completely different, because the large age difference between the teacher and the students seems to be directly proportional to the reluctance in front of digital intelligence. It seems that this approach is common to seniors, not only Romanians, but also those from Japanese countries, for example (Umemuro, 2004). Ultimately, the attitude and comfort felt in relation to any element external to the person are essential predictors regarding the probability of using that object/element. Since both parents and teachers have complained about the need for special pre-training sessions for teachers to use technology, it is obvious that the stringency in this direction should be resolved quickly, so that ICT tools can be used properly in schools.

As a level of general perception, we find a rather open attitude towards new opportunities, with the desire that in the future things will be better organized, so that the online lessons run naturally, without interruptions. Interesting to note, in this context, is the fact that, despite the stated disadvantages, teachers show more confidence in relation to online learning activities, compared to students’ parents. The latter approach a mine rather reluctant to directional decisions, which can tilt the balance of interpretation towards the idea of an expectation that, certainly, everyone wants optimal for the good of their own child.

From a psychological perspective, the online school era has raised waves of opinions for and against, and the present research proves, once again, the need for people of all ages to be able to express their opinions and their desire for better. Withdrawal from natural social contexts prior to the onset of this period meant, including for children, an accumulation of behavioural changes, to the point of bursting into tears or refusing to try to connect to online courses.

With real challenges regarding attitudes, reactions and grievances, the digital courses and the isolation in which the educational actors had to remain represented significant moments in the lives of each of the participants in the present study. As a consequence, a new pedagogical approach was imposed as opportune, through which teachers had to recalibrate their approach to the learning-teaching-evaluation process and, in many situations, even navigate into the unknown without a sufficiently powerful compass.

Bibliography and References

Ceobanu, C. (coord.), Cucoș, C. (coord.), Istrate, O. (coord.), Pânișoară, I.-O. (coord.) (2022). Educația digitală. Iași: Polirom.

Cilliers, Elizelle. (2017). The challenge of teaching generation Z. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences. 3. 188-198. https://doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.31.188198

Cozolino, L. (2013). The Social Neuroscience of Education: Optimizing Attachment and Learning in the Classroom. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Cury, A. J. (2018). Părinți străluciți, profesori fascinanți. (Pais brilhantes, professores fascinantes). București: Editura For You.

English, A. (2016). John Dewey and the Role of the Teacher in a Globalized World: Imagination, empathy, and ‘third voice’. Educational Philosophy and Theory. Volume 48, 2016 – Issue 10: Dewey’s Democracy and Education in an Era of Globalization, 1046-1064.

Farjon, D., Smits, A., & Voogt, J. (2019). Technology Integration of Pre-Service Teachers Explained by Attitudes and Beliefs, Competency, Access, and Experience. Computers & Education, 130, 81-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.11.010

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books, Inc.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203887332

Hofstetter, R., & Schneuwly, B. (2009). Knowledge for teaching and knowledge to teach: two contrasting figures of New Education: Claparède and Vygotsky. Paedagogica Historica. International Journal of the History of Education. Volume 45, 2009 – Issue 4-5: New Education at the Heart of Knowledge Transformations, 605-629.

Kozma, R. (2005). National Policies That Connect ICT-Based Education Reform to Economic and Social Development. Human Technology, 1, 117-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.2005355

Marzano, R.J. (2007). The Art and Science of Teaching: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Instruction (Professional Development). Alexandria: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Păun, E. (2017). Pedagogie. Provocări și dileme privind școala și profesia didactică. Iași: Editura Polirom.

Quay, J. (2016). Not ‘democratic education’ but ‘democracy and education’: Reconsidering Dewey’s oft misunderstood introduction to the philosophy of education. Educational Philosophy and Theory. Volume 48, 2016 – Issue 10: Dewey’s Democracy and Education in an Era of Globalization, 1013-1028.

Rothman, D. (2023, Jan. 2023). A Tsunami of learners called Generation Z (2016). http://www.mdle.net/Journal/A_Tsunami_of_Learners_Called_Generation_Z.pdf

Sălăvăstru, D. (2005). Psihologia educației. Proiectul pentru învățământul rural. (Psychology of Education. Project for Rural Education) Bucharest: Ministry of Education and Research, Romania.

Schaub, H., & Zenke, K. (2001). Dicționarul de pedagogie. Iași: Polirom.

Solomon, L. (2021). Practica pedagogică în școala online – inovare didactică sau imposibilitate pedagogică? Studiu asupra impactului pedagogic. https://edict.ro/practica-pedagogica-in-scoala-online-inovare-didactica-sau-imposibilitate-pedagogica-studiu-asupra-impactului-pedagogic/

Steinhardt, N. (1991). Jurnalul fericirii (Happiness Diary). Bucharest: Humanitas Publishing House.

Stoll Lillard, A. (2017). Montessori. The Science Behind The Genius. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thalhammer, A., Hincha, D. K., & Zuther, E. (2014). Measuring freezing tolerance: electrolyte leakage and chlorophyll fluorescence assays. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 1166, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0844-8_3

Umemuro, H. (2004). Computer attitudes, cognitive abilities, and technology usage among older Japanese adults. Gerontechnology, 3(2), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2004.03.02.002.00

UNESCO (2018). ICT Competency Framework for Teachers, Paris. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265721

UNESCO (2020). Education in a post-COVID world: Nine ideas for public action. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373717/

Windsor, T. D., & Anstey, K. J. (2008). A longitudinal investigation of perceived control and cognitive performance in young, midlife and older adults. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Section B, Aging, neuropsychology and cognition, 15(6), 744–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580802348570

World Health Organization. (2021, March 20). Global school health initiative. Retrieved from www.who.int: https://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/en/

____________________

Author:

Laura Ioniță

Secondary School No. 31, Bucharest

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0003-6604-3900

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-6604-3900

Received: 30.07.2024. Accepted: 10.09.2024

© Laura Ioniță, 2024. This open access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence CC BY, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited:

Citation:

Ioniță, L. (2024). Online Learning in Primary School: Perspectives of Teachers, Students, Parents. Journal of Digital Pedagogy, 3(1) 29-39. Bucharest: Institute for Education. https://doi.org/10.61071/JDP.2462